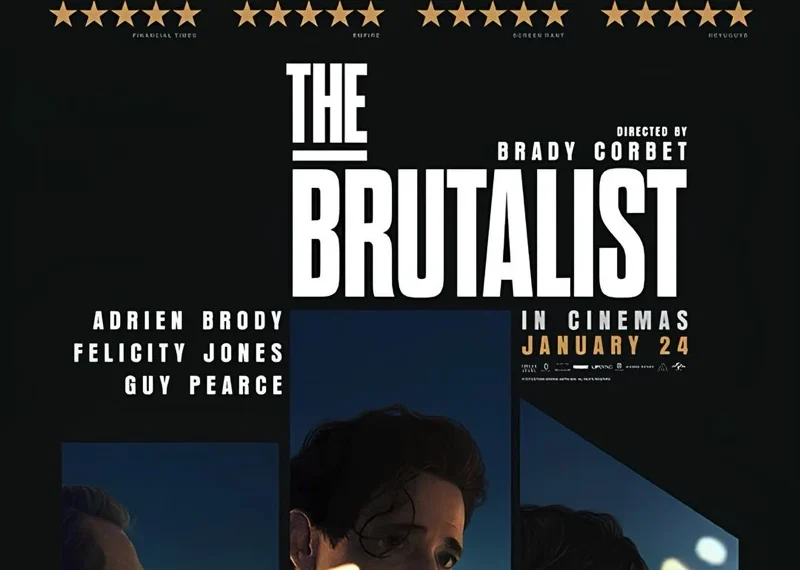

Cast: Adrien Brody, Felicity Jones, Guy Pearce, Joe Alwyn, Raffey Cassidy, Stacy Martin, Isaach De Bankholé and Alessandro Nivola

Genre: Drama

Director: Brady Corbet

In Irish Cinemas: 24th January 2025

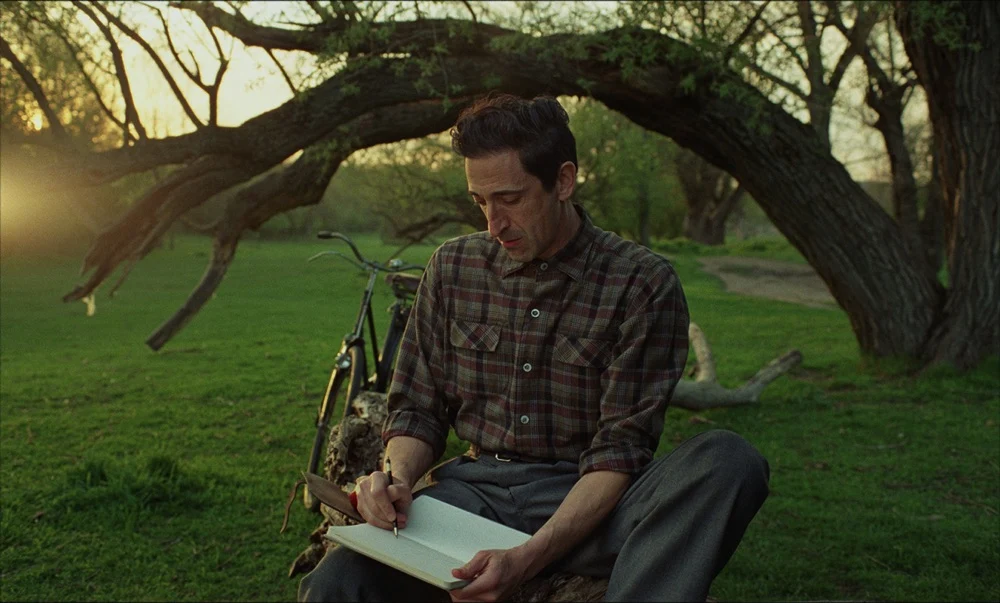

When I first encountered The Brutalist, I found myself using the film’s merciful intermission to google the name László Toth furiously, convinced that the architect at the heart of Brady Corbet’s mesmerising and maddening 215-minute opus must have been an actual figure from the mid-20th century. But, as with Lydia Tár before him, Toth—played with career-defining intensity by Adrien Brody—is a complete fabrication. He emerges fully formed from Corbet’s imagination, a symbol of a broader school of thought, an artistic tradition, and an entire epoch. Corbet’s portrayal of Toth is so detailed, so intricately wrought, that it dupes viewers like me into believing we’ve stumbled upon a hidden truth about something immense and far-reaching.

At least, that’s true for the film’s first half. The Brutalist is split into two chapters: “The Enigma of Arrival” and “The Hard Core of Beauty.” Corbet delights in grand gestures like these, layering his work with signals of its monumental ambition and meticulous construction. To some extent, that boldness is refreshing—why shouldn’t a young filmmaker brimming with ideas and daring aim unapologetically for greatness? Yet the film doesn’t position itself as striving toward the monumental; its assuredness seems to suggest it has already attained that lofty status.

This bravado has a certain charm, but as the second chapter, “Beauty,” plods along, some of that charm begins to wear thin. What had been a compelling, sharply focused narrative about a Hungarian concentration camp survivor’s post-World War II life in America grows muddled and weighed down by its ambition. Corbet’s elaborate construction, initially fascinating, starts to obscure his story’s emotional and narrative clarity. It feels as if he’s built a cinematic Spruce Goose: an intricately designed marvel that, for all its impressive craft, struggles to take flight and land with a practical purpose.

“Arrival” is nothing short of a marvel—at once jarring and frenetic, melancholy and mesmerising. The film draws us into the journey of Toth, who reaches America after an arduous ocean crossing, sailing into New York Harbor with the exhilaration and promise of a new beginning, akin to the moment of birth. Daniel Blumberg’s stunning score heightened this feeling of breathless anticipation, which weaves a sense of giddy unease into the narrative.

Exhausted yet alert, Toth reconnects with his cousin Attila (Alessandro Nivola), a furniture store owner in Philadelphia, and begins to rekindle his architectural career—a craft he once pursued with considerable success before the Nazis rose to power. However, the shadows of Toth’s past linger heavily. His gaunt appearance speaks to the trauma of his wartime experiences, and his heroin use hints at an attempt to numb or escape his memories. Despite this, Toth’s creative spirit and unwavering artistic vision remain intact, driving him forward even as he battles his inner demons.

These pivotal moments of emerging legacy are electric, with Corbet orchestrating a chamber symphony that captures the shimmering possibilities of the New World, all while shadowed by an encroaching darkness. Toth soon finds himself under the patronage of Harrison Van Buren (Guy Pearce), a wealthy industrialist who commissions him for an ambitious project—a community centre that, in truth, is intended to stand as a grandiose monument to Van Buren’s self-serving philanthropy and boundless ego. As viewers, we are armed with enough historical context to distrust a figure like Van Buren instinctively, yet his interest in Toth’s talent carries a seductive allure. Here lies the seductive mythos of America: a place where anyone, no matter their humble or downtrodden origins, can be recognised for their brilliance and rise into the golden glow of opportunity. But, as Corbet’s film so acutely observes, this idealised vision of the American dream is mainly illusory—a fiction belied by the relentless machinery of power and profit that governs the system. Corbet gradually peels back these layers, revealing an increasingly bleak reality as the film unfolds.

The Brutalist examines America and meditates on art—specifically, the compromises artists are often compelled to make in the face of financial demands and patrons’ vanity. Corbet makes a case for art in its purest form, art that can endure and even thrive under the weight of economic pressures and the egotism of its benefactors. The film is a tribute to those who create with sincerity and a mournful reflection on what Corbet may perceive as a fading tradition, particularly in his industry.

This is Corbet’s attempt at a sweeping American epic, crafted on a shoestring budget in Europe without any major studio’s backing. Perhaps there’s a hint of defiance in this—a sense of Corbet saying, “Look what I can achieve without you.” Or maybe it’s a bold repudiation of a system he sees as irredeemably broken. Either way, The Brutalist is a beacon, a torch-lit to guide others as they navigate the precarious terrain of creating lasting, meaningful cinema.

It is unfortunate that Corbet ultimately becomes ensnared in the complexity of his ideas. The second half of The Brutalist is overburdened with events. Tóth is finally reunited with his wife, Erzsébet (Felicity Jones), who carries the deep scars of her Holocaust ordeal, and his relationship with Van Buren takes a harrowing turn. Yet, despite the abundance of narrative developments, this portion of the film feels oddly inert, as though Corbet is either struggling to find a clear direction or deliberately delaying the inevitable conclusion. While undeniably poignant and beautifully executed, the film’s closing moments feel like an afterthought—a kind of deus ex machina that retroactively reveals a concealed subtext Corbet has deliberately withheld. While an enigmatic or discordant ending can often leave a resonant impact, in this case, the abrupt conclusion undermines much of the groundwork laid in the preceding story. And a great deal of groundwork there is.

What remains consistent throughout, however, is the sheer brilliance of Adrien Brody’s performance. He delivers a portrayal that is fiery, wounded, and suffused with intellect, fully embodying a mercurial, soulful man battered by the relentless cruelties of his era. It is a masterclass in acting, matched beautifully by Guy Pearce’s portrayal of Van Buren, whose cold, calculating arrogance evokes a uniquely American breed of predator—part Ayn Rand acolyte, part Calvinist zealot. Brody and Pearce vividly animate Corbet’s exploration of the tensions between art and commerce, between the old world and the new. When these two actors ignite the screen with their performances, The Brutalist achieves an almost mythic grandeur—two virtuosos bringing to life their director’s bold, flawed, and undeniably ambitious vision.

Overall: 7.5/10