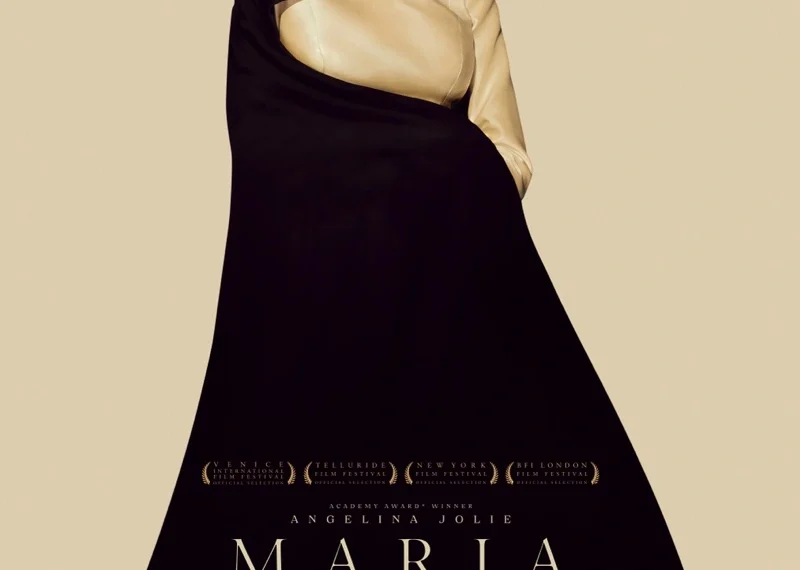

Cast: Angelina Jolie, Pierfrancesco Favino, Alba Rohrwacher, Haluk Bilginer, Kodi Smit-McPhee

Genre: Biography, Drama, Music

Director: Pablo Larraín

In Irish Cinemas: 10th January 2025

Angelina Jolie’s absence from the big screen has stretched to three years, marking a continued retreat from the limelight that began long before her last appearance. Over time, she has been methodically pulling back pieces of herself from the public eye and the magnetic, larger-than-life persona she once embodied on film. The wild-child image that defined her early years, with its edge of rebellion and infamous blood-vial necklaces, is a thing of the past. So, too, is the sultry allure that made her on-screen chemistry with Brad Pitt in Mr. & Mrs. Smith feel like a prelude to their real-life romance.

Today, Jolie has intentionally shed the seductive mystique that once made her a Hollywood icon, redirecting her focus toward roles that highlight her work as a filmmaker, humanitarian, and devoted mother of six. As a celebrity, she has consciously distanced herself from her sex-symbol status, presenting a more measured, layered public identity. As an actor, she has been equally selective, lending her voice to characters like Tigress in the Kung Fu Panda franchise as frequently as she has appeared in live-action films. When she does take on live-action roles, her characters are increasingly characterised by an ethereal beauty and a sense of refined, almost detached suffering.

It’s hard to fault Jolie for fortifying herself against a public that has dissected every corner of her life since her youth, a scrutiny few could withstand. Her decision to create distance feels like an act of self-preservation, an effort to reclaim autonomy after decades under the magnifying glass. Yet, as much as I understand and respect her approach, I can’t deny feeling underwhelmed by this newer iteration of her career.

Jolie’s most compelling performances were defined by her raw, almost predatory energy—a sense that she could leap off the screen and consume the world with sheer force of will. In recent years, however, even in physically demanding roles, such as racing through a forest fire, she seems less fully present, her spark dimmed by the layers of armour she has chosen to wear. While there is dignity in her evolution, it’s hard not to miss the electrifying vitality she once brought to every frame.

That tendency is evident in Maria, the latest film from Chilean director Pablo Larraín, where Angelina Jolie takes on the role of legendary opera singer Maria Callas. It’s easily Jolie’s most ambitious role in years, but rather than signalling a triumphant comeback, it feels like a project tailored to the enigmatic, controlled persona she has cultivated. The performance is steeped in meticulous detail—Jolie reportedly spent months training to sing opera, with her voice seamlessly blended with Callas’s iconic recordings whenever her character performs. Yet, for all its technical precision, Jolie’s portrayal has an undeniable detachment, as though she’s inhabiting a woman who is, in turn, performing the role of Maria Callas.

This layer of removal is partly by design. Maria is the final instalment in Larraín’s trilogy exploring iconic women, following Natalie Portman’s Jackie Kennedy in Jackie and Kristen Stewart’s Princess Diana in Spencer. While Maria is the weakest of the three, it shares its predecessors’ fascination with the intersection of image and identity. The film’s portrayal of Callas, set in Paris during the last years of her life, focuses on a woman who hasn’t performed onstage in years but remains trapped in the act of performing. She sings snippets of arias in the kitchen for her devoted housekeeper, Bruna (Alba Rohrwacher). She plays the imperious diva for a television journalist (Kodi Smit-McPhee), who is later revealed to be a hallucination induced by her reliance on pills.

Like Jackie and Spencer, Maria is less interested in presenting a straightforward biographical narrative than in examining how its central figure navigates the burdens of her public image. Jolie’s performance, for all its aloofness, underscores this theme. She embodies a woman who can never fully separate herself from the roles she plays—both onstage and in life.

All three of these Larraín films explore the dual nature of image—as both a source of immense power and an inescapable prison. They grapple with the paradox of addressing this elevated existential dilemma, acknowledging its absurdity while treating it with the gravity demanded by their subjects. Yet, Maria struggles the most to strike this delicate balance. It wrestles with the tension between the imperious, larger-than-life persona it seeks to project onto its subject and the vulnerability of a woman who spent much of her existence trying to appease those around her.

The narrative flits between the meticulously crafted miniature productions that define Maria’s daily life in 1977 and the grandiose performances she gave onstage in the past. However, these displays—both in her present and her memories—fail to reveal the human essence beneath the theatrical costumes and the luxuriant outfits she wears in everyday life. There is a hollowness at the core, a lack of flesh-and-blood substance to the character behind the spectacle.

Steven Knight’s florid script exacerbates this sense of artificiality. Its dialogue often feels less like an organic part of scenes and more like it was designed to be plucked out for use in a trailer. Consider the exchange between Maria and Feruccio (Pierfrancesco Favino), her ever-watchful butler and one of her two constant companions alongside Bruna. When Ferruccio questions her about her pill consumption, he pointedly asks, “What did you take?” Maria’s reply is as grandiose as it is detached: “I took liberties all my life, and the world took liberties with me.” Later, when Ferruccio finally arranges for Maria to meet the doctor she has been avoiding, the conversation tilts further into melodrama. The doctor reassures her with lofty solemnity: “I need to have a conversation with you about life and death, about sanity and insanity.”

The result is a film that often feels more like a carefully composed tableau than a living, breathing exploration of its subject. It is caught between its ambitions and inability to bring Maria to life fully.

Is Maria genuinely insane? She certainly seems designed to embody chaos—always on the verge of slipping from the care of her devoted domestic staff, stirring up trouble in cafés, and losing herself in elaborate daydreams, such as a conversation with an interviewer named Smit-McPhee, a name she associates with her preferred tranquillisers. When she’s not indulging in these hallucinations, she’s attempting to reconnect with her voice, seeking help from a pianist (played by Stephen Ashfield) who might very well be a figment of her imagination. Yet, despite this erratic behaviour, the film remains surprisingly meticulous with both its central character and the actress portraying her, refusing to acknowledge that there could be something equally tragic and alluring in the spectacle of an opera diva unravelling in her dressing room, desperately searching for one last dose of Quaaludes.

Angelina Jolie delivers an extraordinary performance, looking strikingly glamorous with her sharp cheekbones and elegant brocade housecoats, exuding a near-divine presence, complete with her cat-eye makeup and beehive hairstyle in flashbacks to her affair with Aristotle Onassis (Haluk Bilginer). Maria, too, is presented with an undeniable allure, thanks to the skilful cinematography of Edward Lachman, who brings ’70s Paris to life with the texture of a vintage postcard. Director Pablo Larraín enhances this mood with surreal sequences, such as choirs emerging from the crowds at Place du Trocadéro or orchestras taking their seats on rain-soaked steps. These moments are visually striking, immersing us in a glamorous and dreamlike world.

However, despite the evident craftsmanship poured into the making of Maria, something vital is missing. There is a palpable absence of risk for a film that centres on a performance meant to be celebrated for its boldness and emotional depth. While the spectacle is undeniably grand, there is a lack of urgency or rawness that would make the character’s descent feel more immediate and heartfelt. In the end, the film’s portrayal of Maria is one of meticulous construction, but it never quite captures the unpredictable, dangerous edge of a woman on the brink.

Overall: 6.5/10