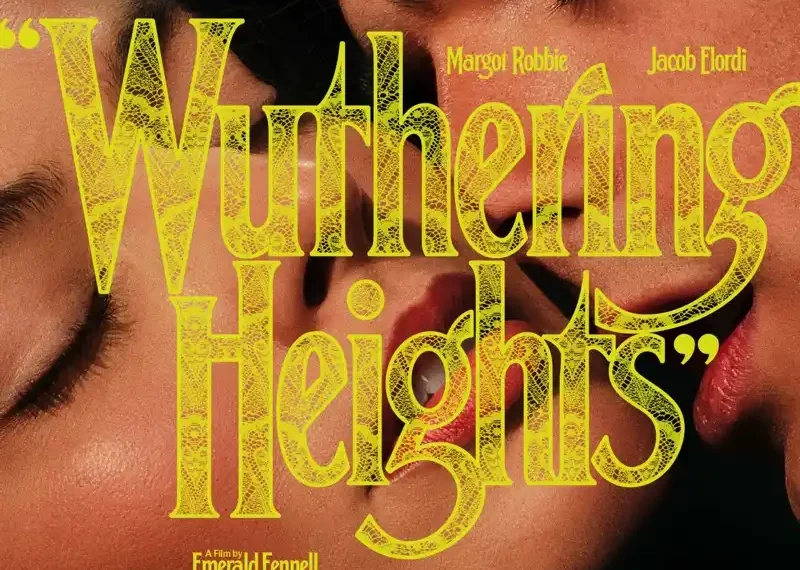

Cast: Margot Robbie, Jacob Elordi

Genre: Drama, Romance

Director: Emerald Fennell

In Irish Cinemas: Now

Few figures in English literature loom as large or as unsettling as Heathcliff, the brooding anti-hero at the heart of Emily Brontë’s Wuthering Heights. Far from a romantic ideal, Heathcliff is a vicious, wounded creature driven by spite, cruelty, and obsession. His only glimmer of humanity lies in his fierce attachment to Catherine Earnshaw, the childhood companion who shapes both his tenderness and his rage. Despite decades of pop-culture romanticising, Brontë’s novel is not a sweeping love story but a bleak Gothic tragedy: a tale of vengeance, social division, and emotional rot set against the harsh Yorkshire moors. With that legacy in mind, Emerald Fennell’s screen version lands not as a bold reinterpretation but as a hollow, disorienting misfire that misunderstands the very bones of the source material.

Fennell has spoken openly about shaping the film through the lens of teenage nostalgia, drawing on memories of reading the novel at fourteen. That youthful fixation might explain the film’s approach because what unfolds onscreen bears little resemblance to Brontë’s layered narrative. Vast swathes of the plot are excised, major characters vanish, and the intricate generational arc is dismantled. Strip away the title and familiar names, and what remains feels less like an adaptation and more like an entirely different story awkwardly draped in borrowed clothes.

The most immediate rupture comes not from casting choices but from structural surgery. One of the novel’s central forces, Hindley Earnshaw, is erased altogether. In the book, Hindley’s jealousy and brutality shape Heathcliff’s psychological descent and fuel the revenge that ripples across decades. Without him, the engine driving Heathcliff’s transformation disappears. In a baffling rewrite, elements of Hindley’s cruelty are redistributed to Mr Earnshaw, fundamentally altering relationships that once carried emotional weight. The result is a version of Heathcliff stripped of motive, drifting through trauma without the scaffolding that once made his darkness tragic rather than arbitrary.

This flattening continues across the narrative. Brontë’s sweeping generational design, in which the sins of the parents echo through their children before finally breaking, is almost entirely discarded. Characters such as Cathy Linton, Linton Heathcliff, and Hareton Earnshaw, who collectively represent the novel’s fragile hope for redemption, are nowhere to be found. Removing them doesn’t merely trim the story; it amputates half of it. Without that second movement, the thematic balance collapses, leaving only a thin, incomplete shell.

Even the characters who remain are warped into unrecognisable forms. Nelly, once a grounded observer guiding readers through chaos, is reshaped into something colder and more antagonistic. Joseph, previously a frightening embodiment of rigid religious zeal, becomes a bizarrely sidelined oddity. Isabella Linton suffers the most drastic overhaul, transformed from a naive victim into a strangely abrasive figure whose arc lacks both sympathy and purpose. These alterations don’t modernise the material; they dilute it, sanding down nuance in favour of erratic reinvention.

At the centre of it all sits a deeply misjudged portrayal of Catherine. Rather than the volatile, untamed spirit who both loves and destroys with equal intensity, this version feels oddly petulant and superficial. The wild arrogance and emotional ferocity that define Cathy in the novel are replaced by a far thinner characterisation, leaving the central relationship adrift. Heathcliff himself fares no better, reduced from a terrifying force of nature to a muted, lovestruck presence lacking menace. Their connection, once defined by toxicity and co-dependence, is reframed as a straightforward star-crossed romance, drained of the danger that made it compelling.

That tonal miscalculation defines the film as a whole. Where Brontë’s story thrives on moral ambiguity and emotional brutality, the adaptation leans heavily into melodrama and overwrought romanticism. Repeated declarations of love and prolonged intimacy scenes attempt to sell a grand passion, but the effect is curiously numbing. Instead of tension, there is monotony; instead of tragedy, sentimentality.

Visually, the film carries flashes of the director’s trademark flair. Lush cinematography ensures every frame is striking, and the score swells with theatrical ambition. Yet the aesthetic often feels at odds with the setting. Synthetic textures, jarring costume choices, and stylised interiors create a strange, almost artificial atmosphere that clashes with the raw earthiness the story demands. Rather than evoking windswept moors and decaying manors, the production design veers toward a fever dream, bold, certainly, but often misaligned with the narrative’s emotional reality.

This clash of tones leaves the film stranded between parody and earnest drama. Moments that seem intentionally absurd sit uneasily beside heavy melodrama, creating a disjointed rhythm that never settles. The visual polish cannot disguise the absence at the story’s core: a lack of thematic gravity. For all its gloss, the film feels oddly weightless.

Ultimately, the adaptation plays less like a reinterpretation and more like an original romance awkwardly masquerading as Brontë. By discarding the novel’s intricate exploration of class, cruelty, inheritance, and moral decay, it replaces complexity with something far simpler and far shallower. Viewers unfamiliar with the source might accept it as a melodramatic love story, but anyone acquainted with the novel’s depth will find little of its spirit intact.

What makes Wuthering Heights endure is its uncomfortable brilliance, its refusal to offer easy redemption, and its fascination with characters who are both monstrous and pitiable. Heathcliff is compelling precisely because he is irredeemable until the very end, and Cathy’s love is powerful because it is destructive. That volatile alchemy is nowhere to be found here. Instead, the film offers a glossy, sentimental retelling that smooths away the rough edges that made the original unforgettable.

In the end, this version feels less like a daring reimagining and more like a misreading elevated to blockbuster scale. The wild, storm-tossed heart of Brontë’s novel has been replaced with a far tamer pulse, one that beats loudly but without depth, fury, or soul.

Overall: 6/10