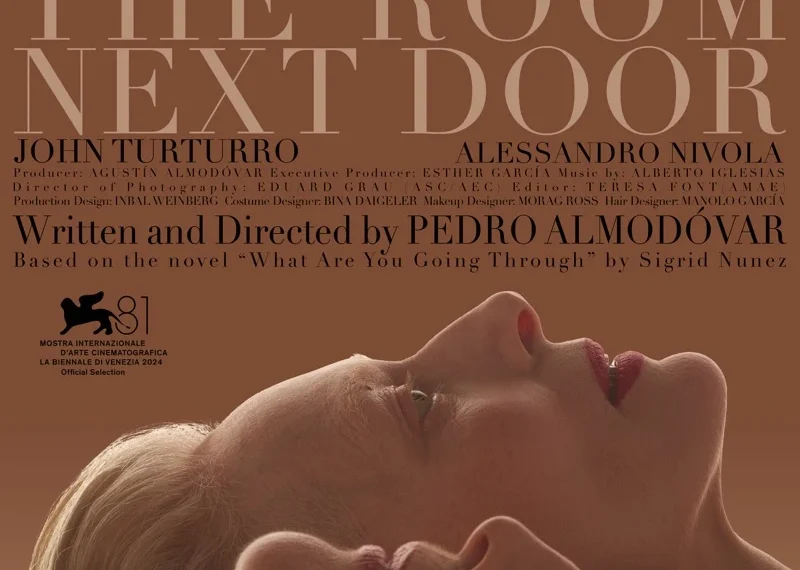

Cast: Julianne Moore, Tilda Swinton, John Tuturro

Genre: Drama

Director: Pedro Almodóvar

In Irish Cinemas: 25th October 2024

In The Room Next Door, Tilda Swinton’s character, Martha, is recovering in what could easily be called the most stunning hospital room ever seen on screen. Although she’s facing the grim reality of inoperable cervical cancer, this is a Pedro Almodóvar film, where even sterile environments are transformed into spaces bursting with life and beauty. Martha’s room is adorned with rich autumnal wallpaper, overflowing bouquets, and a striking lime green chair, all set against a breathtaking Manhattan skyline view. At one point, the scene becomes even more surreal as pink snow gently falls outside her window. The visual impact is striking when Julianne Moore’s character, Ingrid, a writer with an iconic burgundy lip, visits Martha in an early scene. The embrace between the two is like a study in colour theory: Swinton reclines in bed, dressed in a vibrant red jacket and electric blue pants. At the same time, Moore steps in wearing a burgundy coat and carrying a navy intrecciato bag. It feels as though their roles have been inverted, with Martha, despite her terminal illness, dressed in the boldest colours, while Ingrid, the seemingly healthy friend, appears in more subdued tones. The Room Next Door is a profoundly reflective meditation on mortality, but in true Almodóvar style, this exploration is infused with vivid visual fantasy. It becomes less about death as a bleak inevitability and more about the idea of directing one’s final moments with the same care one might apply to staging a scene in a film—choosing the time, the place, and even the clothes in which to face the end. The film is at once rapturous and contemplative, full of rich, sensual details that elevate it from a meditation on death to an act of aesthetic transcendence.

The Room Next Door is adapted from Sigrid Nunez’s novel What Are You Going Through and marks Pedro Almodóvar’s first English-language feature. Though he has experimented with the language in recent shorts like The Human Voice and Strange Way of Life, this is a more substantial foray into English filmmaking. The film is a companion to Almodóvar’s 2019 semi-autobiographical work Pain and Glory, which centred on an ageing Spanish director whose declining health and creative stagnation leave him feeling purposeless. In The Room Next Door, however, the lens shifts to Martha, a former war correspondent whose struggle is more external. Martha, now undergoing chemotherapy, finds herself unable to write, read, or listen to music—activities that once defined her. The chemotherapy has robbed her of focus and, along with it, a piece of her identity. This sense of loss echoes the creative and physical decline themes seen in Pain and Glory, though it’s experienced secondhand by Ingrid, the film’s narrator. Ingrid is an author who has recently written a book about her fear of death but is forced to confront this fear directly when Martha, an old friend, asks her to accompany her on a trip to the Catskills. Martha, weakened by illness, plans to end her life on her terms during this retreat, making the film an exploration of mortality and the lessons the living learn from the dying. Where Pain and Glory felt profoundly personal and intimate, The Room Next Door adopts a more contemplative tone, observing death from a slightly removed perspective through a companion’s eyes rather than the afflicted themselves. This shift in perspective gives the film a quieter, more reflective resonance as it explores what it means to bear witness to another’s final chapter.

While touching on themes of acceptance and finality, the film never slips into the overly sentimental tone that one might expect. Martha’s quiet reckoning with her situation is arguably the least impactful aspect of a story filled with strange and captivating moments. There’s a sense that the director, like his characters, struggles to embrace the idea of closure fully. Much like in Pain and Glory, the past bursts onto the screen with a vividness that overshadows the present. Martha’s memories are haunting—whether it’s her encounter with a Carmelite friar in war-torn Baghdad, who was once romantically involved with a colleague, or the tragic story of her child’s father. This Vietnam veteran died in a house fire as a result of his battle with PTSD. Interspersed with these heavy recollections are moments of dark humour and absurdity. In one scene, Ingrid, Martha’s friend, confides in a gym trainer near Woodstock about her friend’s impending death. The trainer, attempting to offer comfort, admits that he would hug her if not for the legal risks of touching clients. It’s a perfect example of the film’s knack for undercutting deep emotion with dry wit. Then, there’s Damian, played by John Turturro—a man who has dated Martha and Ingrid at different times. A writer like Martha, Damian has made his name as a climate pessimist, his bleak outlook on the future contrasting sharply with Martha’s serene acceptance in her remaining days. The interplay between these characters reflects how people cope with the inevitability of both personal and global endings.

Much of the film revolves around its two female leads’ intimate and evolving relationship. The story unfolds primarily within the confines of a hospital room, then expands to their luxurious city apartments, and finally transports them to a spacious, minimalist vacation home nestled in the woods. Here, Ingrid and Martha, once wild in their youth, spend their remaining time together until Ingrid chooses to let go. These scenes of shared reflection, laughter, and sorrow are steeped in tenderness. Their efforts to recapture their youthful bond are beautiful, not merely because of the picturesque setting but because of the raw emotional connection that surfaces between them. Swinton, playing Ingrid, brings depth to her performance by blending moments of calm with flashes of sharp wit and subtle frustration, avoiding the trap of playing only a serene, angelic figure. Moore, as Martha, offers a more outwardly awkward contrast—her responses often come too quickly or brightly, as though she’s grappling with her discomfort and anxiety over what is happening to her friend. One of the film’s most visually striking moments comes when Ingrid climbs into bed with Martha, the two women lying side by side. Their faces, pressed together on adjacent pillows, form a disjointed, Picasso-like portrait that reflects their closeness and the complexity of their differences. However, what makes The Room Next Door most unexpected is its ending. Rather than delivering a clear, conclusive resolution, the film takes a few unexpected turns and fades out somewhat ambiguously, leaving the audience with incompleteness. Yet, in a way, this open-mindedness is a fitting tribute to the film’s spirit, suggesting that life and its stories are rarely wrapped up neatly. It also hints at Almodóvar’s desire to keep exploring new narratives.

Overall: 6/10