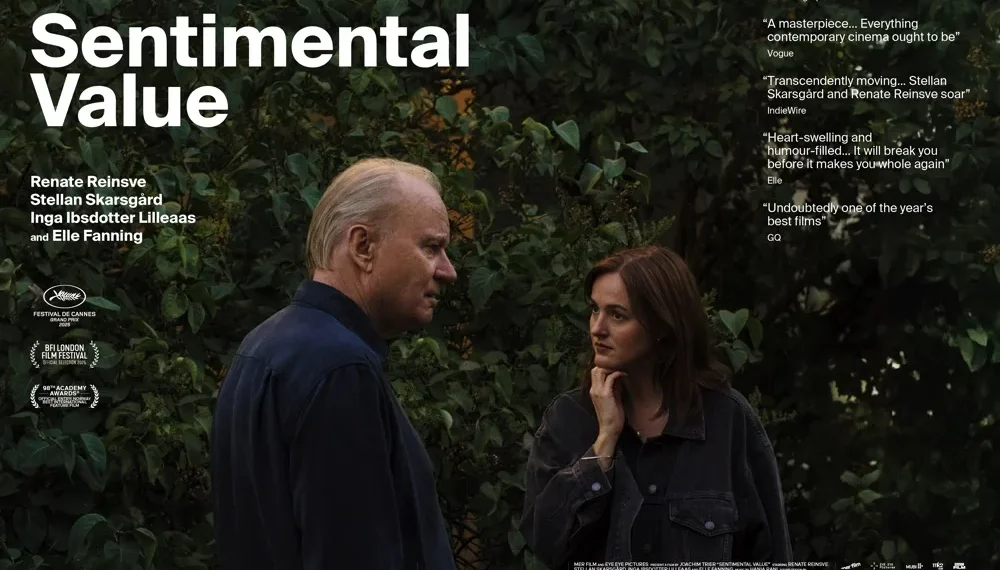

Cast: Renate Reinsve, Stellan Skarsgård, Elle Fanning, Inga Ibsdotter Lilleaas, Anders Danielsen Lie

Genre: Drama

Director: Joachim Trier

In Irish Cinemas: 26th December 2025

Norwegian filmmaker Joachim Trier returns with another quietly devastating Scandinavian drama, but Sentimental Value signals a subtle yet significant evolution in his work. Long celebrated for the Oslo Trilogy Reprise, Oslo, August 31st, and The Worst Person in the World, Trier has built a career excavating the anxieties of young adulthood and the ache of becoming oneself. Here, he widens his emotional and generational scope. The result is a restrained yet piercing meditation on sisterhood, inherited trauma, and the fraught possibility of reconciliation, as a fractured family attempts to heal through the very medium that once helped tear it apart: cinema itself.

The film centres on sisters Nora (Renate Reinsve), a tightly coiled theatre actor defined by discipline and emotional vigilance, and Agnes (Inga Ibsdotter Lilleaas), a calm, quietly fulfilled academic historian. Their uneasy balance is disrupted following their mother’s death, which draws back into their orbit their estranged father, Gustav (Stellan Skarsgård), a revered filmmaker whose artistic legacy far outweighs his record as a parent. Gustav’s return is not accompanied by apology or introspection. Instead, he offers Nora the lead role in his new film, a thinly disguised dramatisation of his own mother’s suicide. It is a grandiose, self-serving overture, and a brutal reminder that his daughters’ pain has always been secondary to his creative impulse.

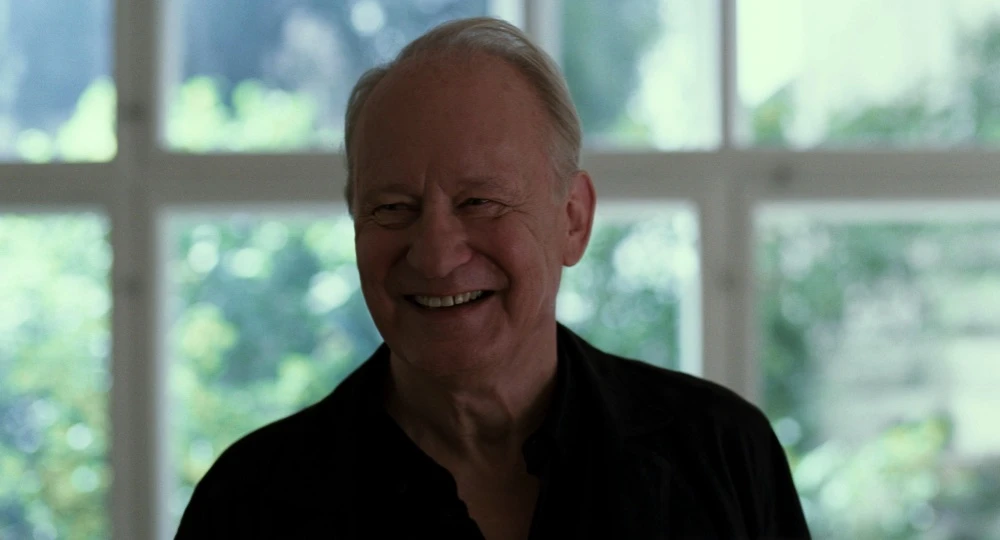

Nora’s rejection of the role becomes one of Sentimental Value’s most electrifying sequences, staging a controlled yet venomous confrontation between Reinsve and Skarsgård. Trier allows silence and micro-gesture to do the heavy lifting: a smug half-smile meets a gaze sharpened by years of accumulated resentment. Reinsve once again proves herself Trier’s most precise collaborator. At the same time, Skarsgård delivers one of his most layered performances in recent memory, veering effortlessly between darkly comic self-regard (his grotesquely inappropriate habit of gifting his grandson DVDs of The Piano Teacher and Irreversible) and quiet emotional devastation. The exchange reaches its most cutting point with Gustav’s confession to Nora: “I recognise myself in you.” It lands not as praise, but as a curse.

After Nora refuses, Gustav casts Rachel Kemp (Elle Fanning), a bright, eager American star and longtime admirer, in the role intended for his daughter. What follows is a sharp meta-commentary on cinema’s uneasy relationship with truth, the distance between lived experience and its aesthetic reproduction. When Rachel performs a monologue shaped by Nora’s pain, the emotional specificity collapses into approximation. The scene is not poorly acted so much as fundamentally hollow, exposing the limits of empathy when experience is replaced by interpretation. Forced to watch a stranger embody a version of herself, Nora is confronted with an image she neither recognises nor can fully escape.

The film-within-the-film is rendered with convincing tactility, aided by Kasper Tuxen’s raw, textured cinematography, the kind of austere visual language Gustav would champion. At times, however, Sentimental Value risks indulging too heavily in its own wistfulness. In moments where Trier’s faith in art as a redemptive force asserts itself most strongly, the sentiment threatens to dilute the film’s otherwise unflinching emotional clarity.

Still, Trier ultimately arrives at a place bracing and honest. In a final passage stripped of dialogue and decorative flourish, Sentimental Value achieves a resolution that is both devastating and deeply restrained. Cinema and healing briefly align not as absolution, but as acknowledgement. The film closes on a note that is at once heavy and tender, lingering long after the screen goes dark, a quiet testament to what art can reveal even when it cannot repair.

Overall: 8/10