Reviewed on 30th January at the 2025 Sundance Film Festival

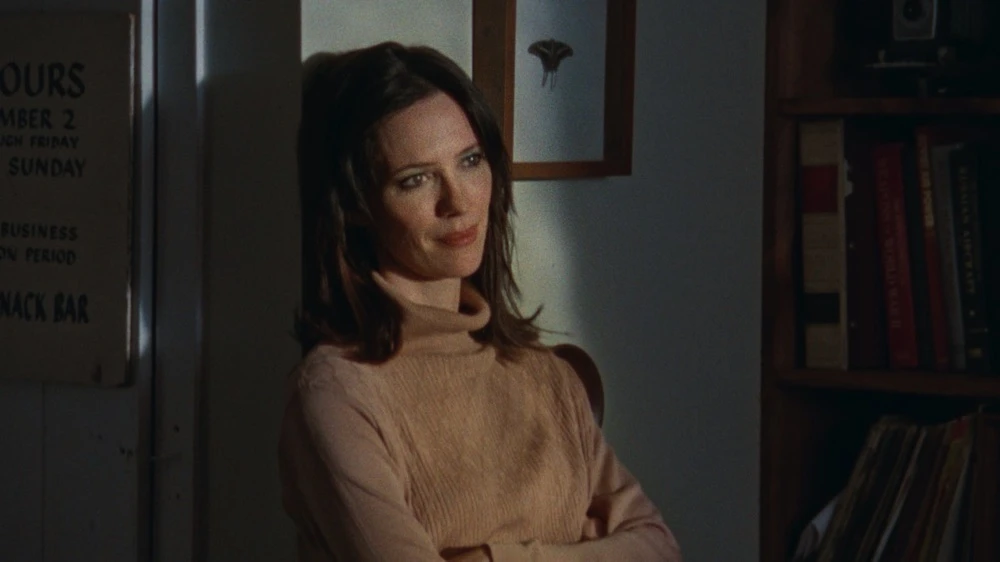

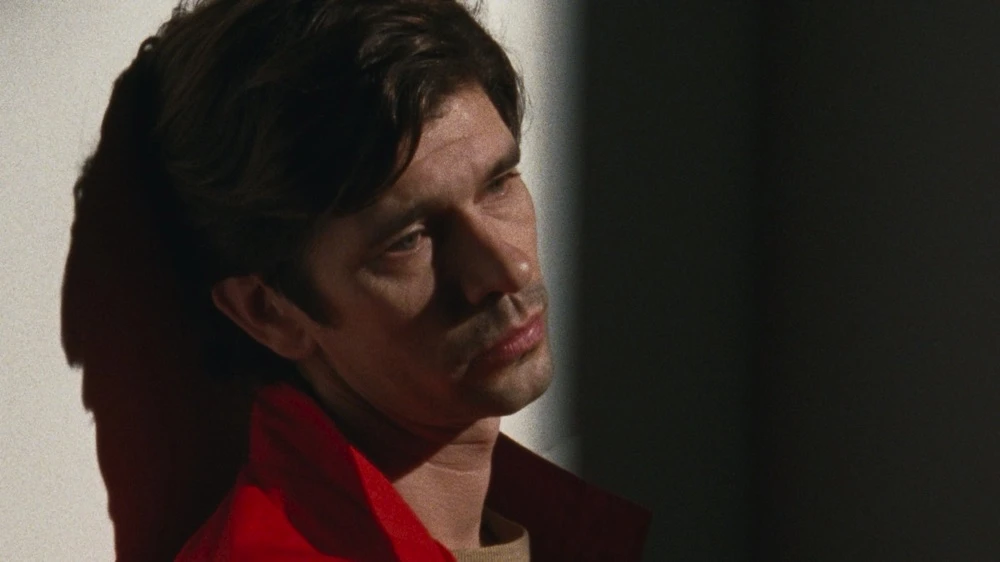

Cast: Ben Whishaw, Rebecca Hall

Director: Ira Sachs

Genre: Biography, Drama, History

In Irish Cinemas: 2nd January 2026

Peter Hujar was an exceptionally gifted photographer and an impeccably stylish gay figure moving through the art world of the 1970s and 80s. Circling the same downtown New York milieu as Andy Warhol and Robert Mapplethorpe, he belonged to a small, fashionable network of artists, writers and thinkers. In 1974, he became the subject of an unusual nonfiction exercise devised by writer Linda Rosenkrantz: he went to her apartment and, speaking into a tape recorder, narrated everything that had happened to him over the course of a single day.

The original recording has since vanished, but a transcript remained. That document resurfaced decades later as Peter Hujar’s Day, published three years ago and now adapted for the screen by Ira Sachs. Sachs turns it into a tightly contained, verbatim chamber film set entirely within Rosenkrantz’s apartment, occasionally shifting rooms, once or twice drifting onto the roof to gaze at the city beyond. The film is deliberately styled to resemble a period artefact: faux 16mm textures, clumsy edits, and visible scratches that evoke a physical film print from the era.

Rebecca Hall plays Rosenkrantz, whose role is mainly to prompt, listen, and register reactions, alert, curious, and gently amused, with an undercurrent of sympathy. Ben Whishaw inhabits Hujar, recounting what he initially dismissed as an unremarkable day but which slowly reveals itself as densely packed with anxiety and activity: fretting over money, health, and exhaustion; visiting Allen Ginsberg to photograph him for the New York Times in an encounter tinged with the absurd; returning home; sharing Chinese food with a friend; and ending the night by playing Bach on the harpsichord.

Whishaw’s performance is restrained and precise. He keeps the delivery flat and observational, rarely signalling emotion directly, letting feeling seep through almost imperceptibly. This is a far cry from a conventional dramatic monologue; there are no crescendos of confession, no cathartic tears or bursts of laughter, no scripted moments of revelation. Sachs resists shaping the material into a traditional arc, leaving the audience to sift through the flow of recollection and identify the small, Bloom-like moments that matter.

One such moment occurs during the Ginsberg shoot. The poet unsettles Hujar by chanting mid-session and by flippantly suggesting that Hujar perform oral sex on his following photographic subject, William Burroughs. Hujar reports this without commentary or complaint, as though registering it as just another oddity, an implicit reminder of how Ginsberg’s fame insulated him from restraint. Throughout the monologue, Hujar casually name-drops figures from his circle. Among the least significant, he suggests, is his journalist friend Fran Lebowitz, whom he thinks might be persuaded to write an introduction to his next photo book. However, he admits he would much rather have Susan Sontag. “I’ve always had a star thing,” he confesses, embarrassed by his own ambition. There is an unspoken irony here: from a future vantage point, Lebowitz would eclipse nearly all of them in public recognition.

Hujar’s persistent exhaustion becomes another thread. Rosenkrantz wonders aloud if his diet is to blame. How many vegetables does he eat? Very few, he shrugs. He chain-smokes relentlessly, living with what feels like a permanent nicotine haze. No one, it seems, is taking care of him; whether that means he is lonely remains unresolved.

Ageing, too, creeps in. Hujar complains of becoming longsighted; Rosenkrantz commiserates with her about her bursitis. Both are startled by these intrusions of physical decline, things they once assumed belonged only to other people. This prompts Hujar to recount a darkly comic anecdote about photographer Maurice Hogenboom, who stepped back during a shoot in Brazil to get a better look and promptly fell off a cliff to his death.

Out of these fragments emerges something like a quiet revelation. Hujar realises perhaps only as he speaks that making art requires time: time to reflect, time to work, time to stand and look. This recognition feels newly formed, as if the act of narrating his day has made it visible to him.

So what does the film ultimately amount to? Its appeal is necessarily narrow, and despite the intelligence of Hall and Whishaw’s performances, neither is pushed toward apparent virtuosity. Yet the project remains quietly compelling as an experiment, an attempt to reconstruct, minute by minute, the texture of a vanished life, and to preserve the ordinary consciousness of a particular person in a specific place, before history could flatten it into legend.

Overall: 6/10