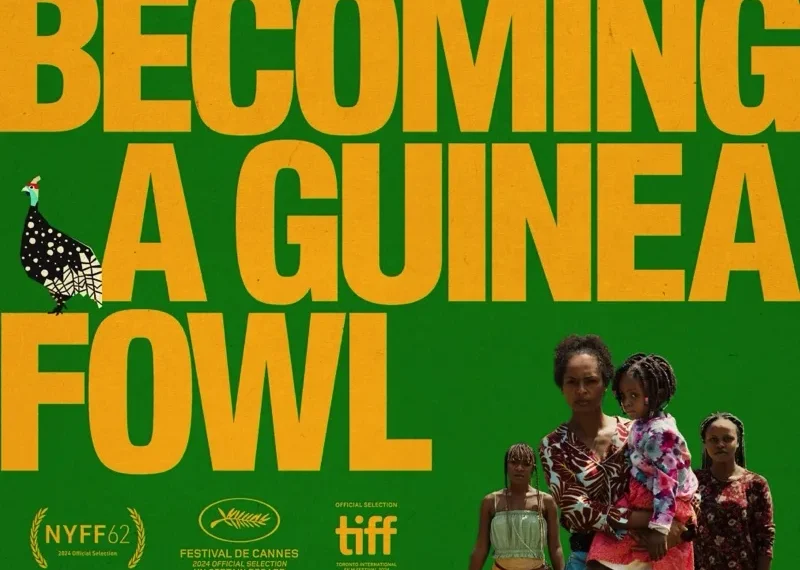

Reviewed on May 16th at the 2024 Cannes Film Festival – Un Certain Regard section. 99 Mins

Cast: Susan Chardy, Roy Chisha, Blessings Bhamjee

Genre: Comedy, Drama

Director: Rungano Nyoni

In Irish Cinemas: 6th December 2024

Rungano Nyoni rose to prominence in 2017 with her critically acclaimed film I Am Not a Witch, which premiered in the Directors’ Fortnight section at the Cannes Film Festival. This striking debut is a darkly comedic and surreal exploration of societal norms, centering on Shula, a young Zambian girl accused of witchcraft. Faced with an impossible choice—either admit to being a witch or be transformed into a goat—Shula reluctantly accepts the label of “witch” and is subsequently sent to a camp where women accused of sorcery are held. There, she is exploited as both a laborer and a symbol of superstition, with her life manipulated by those in power.

Through this poignant narrative, Nyoni weaves sharp satire and evocative storytelling to interrogate the tension between tradition and modernity in contemporary African society. The film serves as a lens through which she examines the oppressive weight of superstition and the uneasy intersection of belief systems and social progress, offering a critique that is both deeply rooted in cultural specificity and universally resonant.

The title On Becoming a Guinea Fowl hints at a similarly whimsical or symbolic tone as Nyoni’s previous work, but the film takes a more somber and weighty approach. The main character, also named Shula, anchors a narrative that delves into the tensions between age-old traditions and the encroachment of modernity. Using a family funeral as its narrative foundation, Nyoni crafts a deliberately paced, slow-burning drama. The story quietly builds layers of complexity and emotional depth, leading the audience toward an unexpected and deeply moving climax. This is a mature, thought-provoking exploration of cultural dynamics and personal identity.

The story opens with Shula (Susan Chardy) navigating a winding country lane in her family’s rural village after attending a costume party. Her Afro-futurist attire—a silver headset paired with a billowy, blueberry-shaped jumpsuit—creates a striking contrast against the serene, pastoral backdrop. The juxtaposition becomes even more pronounced when she spots a figure sprawled in the middle of the road. Alarmed, Shula stops her car and steps out to investigate, only to discover that the lifeless body belongs to her uncle Fred.

Shocked and panicked, she immediately dials her mother to break the news. However, her mother dismisses the grim reality with an almost absurdly casual denial. “Fred can’t die,” she insists. “Just sprinkle some water on him.” But no amount of magical thinking can alter the truth—Fred is undeniably dead. As Shula wrestles with her mother’s refusal to accept the situation, a pickup truck arrives to unceremoniously remove Fred’s body, leaving Shula to process the surreal turn of events alone.

Much like the Dogme film Festen, the story truly begins at Fred’s funeral, where director Nyoni immerses us in the rich traditions and ceremonial intensity of a Zambian send-off. The proceedings take on an almost surreal quality as death itself appears to crawl into Shula’s mother’s home, symbolized by women from the family entering on their hands and knees. These women, referred to as “aunties,” dominate the narrative from this point forward, expressing their grief with unrestrained wailing and dramatic gestures. This raw emotional outpouring starkly contrasts with Shula’s calm and distant demeanor, which quickly arouses suspicion among the mourners. “Her eyes are so dry. She doesn’t look like someone who’s just seen a corpse,” one remarks, encapsulating their unease with her perceived indifference.

From her detached vantage point, Shula observes the intricate and often unsettling dynamics of the funeral preparations. Her attention is particularly drawn to the escalating mistreatment of Fred’s widow, who is harshly accused of being a neglectful wife, guilty of failing to cook for her late husband. These accusations begin to unravel troubling truths about Fred himself, including his disturbing preference for progressively younger women. Shula soon realizes that the family is either complicit in this knowledge, like the aunties, or willfully ignorant, like her estranged father (played by Henry B.J. Phiri). Her father, nonchalantly lounging in a swimming pool within a nightclub that bizarrely doubles as a library, brushes off her concerns. “Do you want to dig up the corpse and confront it?” he asks, drink in hand, signaling his preference for avoiding uncomfortable truths.

Nyoni’s film maintains a measured and composed tone throughout, resisting the temptation of an emotional crescendo. This restraint makes the climactic revelations all the more impactful. The film’s enigmatic conclusion provides some insight into its mysteries—such as its elaborate title and the identity of a young girl Shula glimpses staring curiously at Fred’s lifeless body—yet it resists offering tidy resolutions. The ambiguous ending resonates emotionally, even as it leaves much unresolved. For Fred’s family, his death marks the close of an unseemly chapter, but for Shula, it might just signal the beginning of a deeper reckoning.

Overall: 6.5/10