Reviewed on 29th August at the 82nd Venice International Film Festival 2025

Cast: Lee Byung-hun, Son Ye-jin, Park Hee-soon, Lee Sung-min, Yeom Hye-ran, Cha Seung-won, Yoo Yeon-seok

Genre: Comedy, Crime, Drama, Thriller

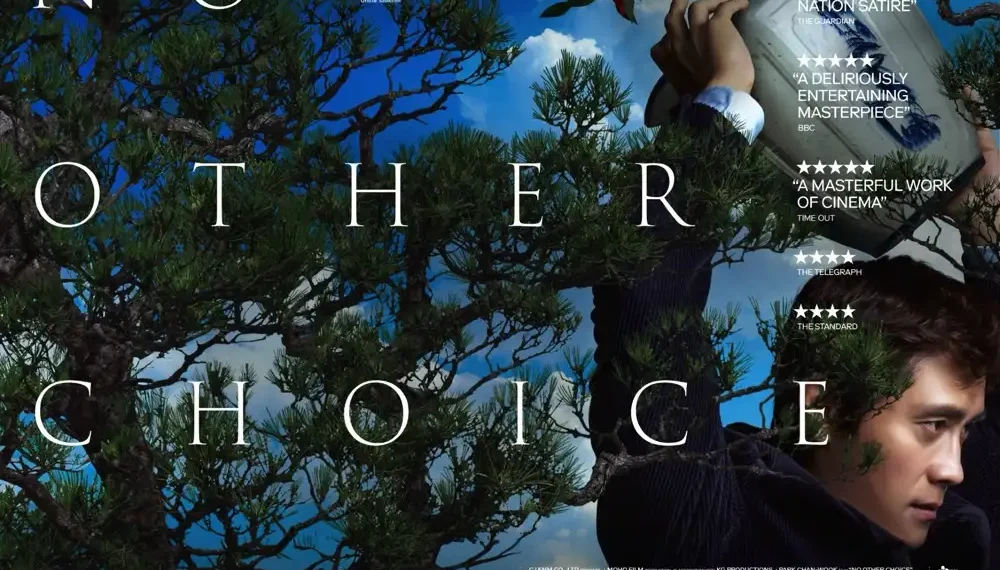

Director: Park Chan-wook

In Irish Cinemas: 23rd January 2026

What’s usually sold as a crisis can be reframed as an opportunity: a forced pause to reassess your life, recalibrate your priorities, and maybe become a better version of yourself. Park Chan-wook, however, has little interest in that brand of self-help optimism. In his caustic thriller No Other Choice, reinvention takes a far more efficient form. When career doors slam shut, the quickest way forward isn’t networking, humility, or personal growth; it’s removing the competition entirely.

The film, which debuted at Venice and later captured the International People’s Choice Award in Toronto, opens on familiar, almost comforting ground. Man-su (Lee Byung-hun) embodies corporate stability. He’s spent a quarter century climbing the ranks at Solar Paper, earning accolades like “Pulp Man of the Year” and securing the kind of upper-middle-class life that feels permanent. He lives in a handsome home rich with personal history, grills in the yard with his wife Miri (Son Ye-jin) and their two children, and allows himself a quiet moment of pride. This is what success looks like, or so he thinks.

That illusion collapses quickly. Solar Paper is absorbed by an American conglomerate, and Man-su is abruptly shown the door. He promises his family and himself that he’ll land a comparable position within a few months. A year passes. The job offers never come. The mortgage bills do. Anxiety metastasises into desperation.

At first, No Other Choice appears poised to be another sober reflection on economic precarity and middle-aged obsolescence. Then Park veers sharply into something darker and far more perverse. Shut out of the executive class and stewing with resentment toward a smug rival manager at Moon Paper (Park Hee-soon), Man-su decides that the job market doesn’t need to be navigated; it needs to be cleared. His solution is chillingly pragmatic: eliminate the man currently holding the position he wants, and quietly dispose of anyone else who might be qualified to replace him.

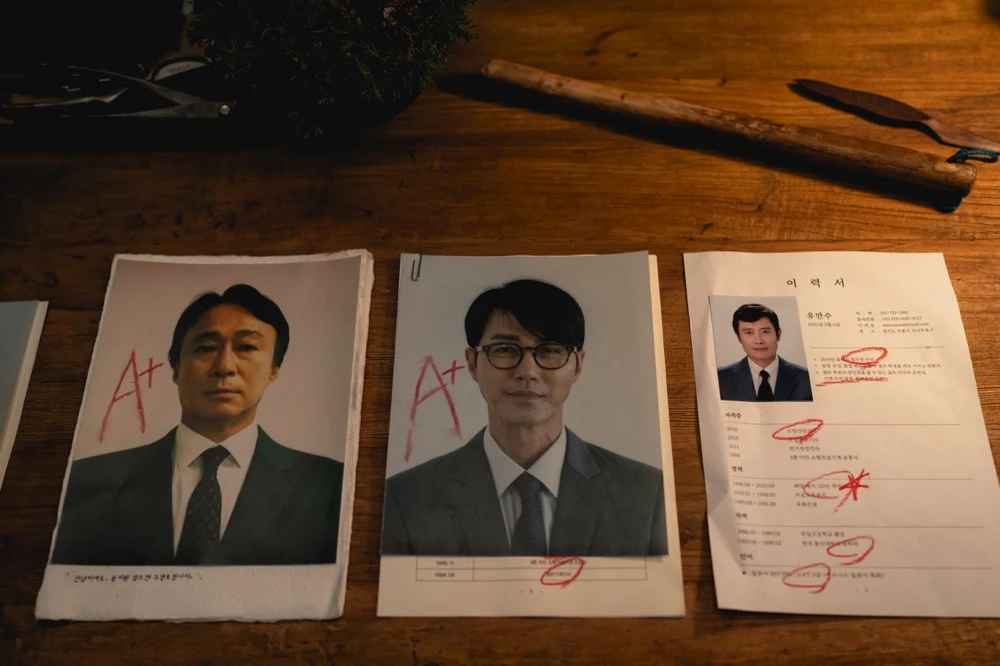

To pull this off, Man-su constructs a grotesque parody of corporate recruitment. He creates a fake paper company and invites résumés from unemployed executives like himself. He studies their credentials carefully, identifying those who outshine him on paper and marking them for death. In his mind, this isn’t madness so much as strategy.

The premise is as outrageous as it is unsettling, and it has literary roots. Park adapts Donald E. Westlake’s 1997 novel The Ax, previously filmed by Costa-Gavras, to whom Park dedicates this version. But while Man-su has mastered the slow, deliberate craft of papermaking in an increasingly digital world, he finds that murder is not so easily systematised. His assassination attempts unfold less like sleek thrillers and more like grim slapstick, with Park staging bungled attacks that leave Man-su bruised, panicked, and barely alive.

This tonal balancing act feels deliberate. Early in his career, Park built his reputation on savage revenge stories like Sympathy for Mr Vengeance and Oldboy. More recently, with films such as The Handmaiden and Decision to Leave, he’s embraced refined visuals and prestige-movie elegance without abandoning his fascination with moral rot. No Other Choice fuses those impulses. It’s polished and controlled, but viciously cynical beneath the surface.

Despite the growing body count, the film often leans toward satire rather than despair. Park delights in exposing Man-su’s insecurities and absurdities, from paranoid domestic confrontations to humiliating attempts to reassert masculine authority. The movie remains flirtatious and darkly playful even as the police begin circling and suspicion mounts.

Crucially, Lee Byung-hun refuses to let Man-su remain a tragic victim. Any early sympathy evaporates as it becomes clear that his hesitation isn’t rooted in guilt but in inexperience. He doesn’t struggle because he has a conscience; he struggles because he hasn’t perfected the technique yet. Park’s provocation is blunt and unsettling: in a world governed by ruthless competition, even murder can be treated as a learnable skill. Apply yourself, practice enough, and results will follow.

Disturbingly, Man-su’s transformation brings unexpected benefits. His violent assertiveness revitalises his marriage, strengthening his connection with Miri, a woman who has already rebuilt her life once before. Professional success and domestic harmony, the film suggests, may be fueled by the same toxic engine.

None of this is entirely unprecedented. The film’s portrait of a workforce hollowed out by automation, downsizing, and corporate indifference echoes familiar cultural touchstones, from Parasite to Breaking Bad. Yet No Other Choice is most incisive when it steps away from its audacious set pieces and focuses on quieter humiliations, the slow erosion of dignity, identity, and empathy under an economic system that treats people as expendable material.

In the end, Park’s metaphor is brutally clear. Just as trees are felled, pulped, and processed to produce the paper Man-su reveres, human beings are ground down by the same machinery. Some are discarded. Others learn to sharpen themselves into weapons. Either way, everyone winds up in the shredder.

Overall: 7.5/10