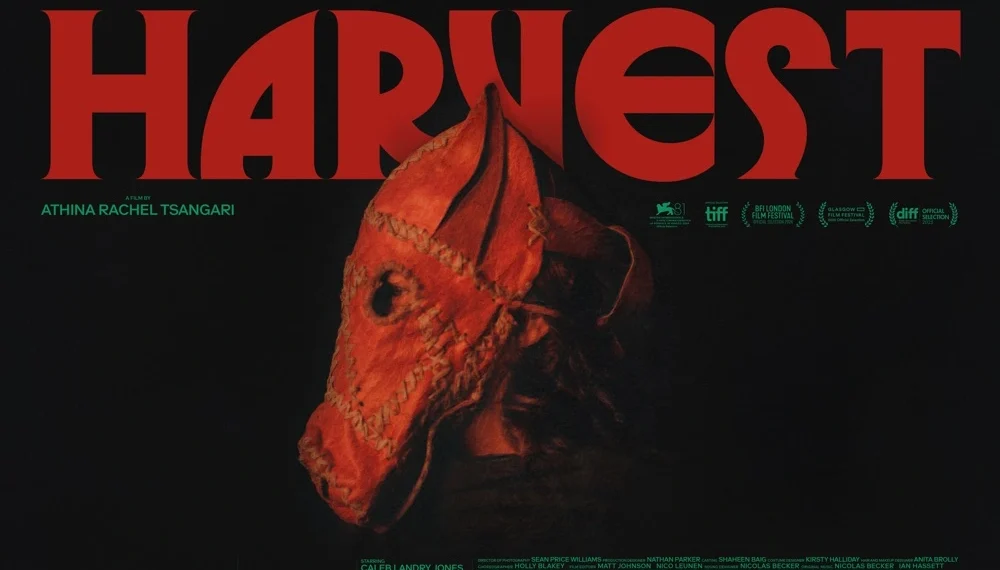

Cast: Caleb Landry-Jones, Harry Melling, Rosy McEwan, Arinzé Kene, Thalissa Teixeira, Frank Dillane

Genre: Drama, History

Director: Athina Rachel Tsangari

In Irish Cinemas: 18th July 2025

Anticipation ran high for this film — the English-language debut of Athina Rachel Tsangari, a central figure in Greece’s New Wave cinema, adapting a novel by Jim Crace. With her reputation for intelligent, idiosyncratic filmmaking, expectations were for something bold and unsettling. Instead, what emerges is a visually indulgent but dramatically hollow folk tale, a would-be allegorical fable set in an ambiguously medieval hamlet straddling the foggy edges of Scotland and Somerset. Or rather, an invented nowhere, steeped in pastoral cliché and faux-archaic ritual, where golden light bathes every hillside and the camera lingers with near-comic reverence on close-ups of beetles and bees.

The film unfolds in this stylised backwater, where dirt-smudged villagers prepare for an annual harvest celebration. They don’t wear eccentric hats and wear Dionysian masks in a half-hearted pageant of fertility rites. Central among the local customs is a surreal and supposedly ancient rite in which children are made to bash their heads against a ceremonial stone — a crude metaphor for indoctrination, social obedience, and the suppression of ambition. This absurd tradition, which reportedly has some historical basis, pushes the film uncomfortably into Lars von Trier-esque territory — a zone of cruel mysticism wrapped in art-house pretension.

Caleb Landry Jones stars as Walter Thirsk, a reticent villager with a murky past who has settled into a quiet life alongside a local woman (Rosy McEwen). Jones, typically a compelling presence, delivers a performance so lethargic and mannered that it borders on parody. His accent — somewhere between Robin Hood’s Sherwood Forest and Monty Python’s peasants — is a distraction throughout, and his slow, affectless delivery drains already inert scenes of what little energy they might have held.

Walter is closely tied to Master Kent (Harry Melling), the affable and ineffectual landowner who seems more interested in peacekeeping than justice, especially when the village barn is mysteriously set ablaze. Rather than investigating the fire, the townsfolk default to blame: three strangers are rounded up, including a woman (whose head is shaved as a mark of exile) and two Scottish-sounding men who are thrown into the stocks for reasons that are never made entirely clear.

But these scapegoats soon become narrative afterthoughts. The real conflict emerges quietly: Kent, despite his gentle demeanour, is secretly pursuing a hidden agenda. He has summoned a cartographer named Earle (Arinzé Kene) to map the region — not as a gesture of knowledge or stewardship, but as a prelude to enclosure and economic upheaval. The goal is to transition the land into sheep pasture, a profitable enterprise that will dispossess the villagers and leave them destitute. The scheme is being orchestrated by Kent’s cousin, Jordan (Frank Dillane), a smug and mercenary figure poised to assume complete legal control.

Walter, increasingly uneasy, sees the map not as a tool of clarity but as a tool of erasure — a reduction of lived space into lines and borders, what he calls a “flattening” of the land. The fire, it seems, has provided a convenient pretext for accelerating these changes, though curiously, the catastrophe itself leaves little visible impact on village life.

For all its lofty ambitions and stylised trappings, the film remains frustratingly inert. Tsangari’s direction is listless, the pacing sluggish to the point of torpor, and the performances uniformly stilted. Moments that should land with emotional or thematic weight pass by in a fog of affectation. Even when the narrative lurches toward a grotesque and violent crescendo — one that exposes the raw nerve of patriarchal violence and feudal cruelty — the actors seem barely conscious, as if sleepwalking through a nightmare no one believes in.

What could have been a searing parable of displacement and exploitation instead feels oddly disengaged, a muddled exercise in aestheticised misery. In attempting to construct a mythic past, the film instead conjures a stylised void — a beautiful but soulless limbo where meaning never quite takes root.

Overall: 5.5/10