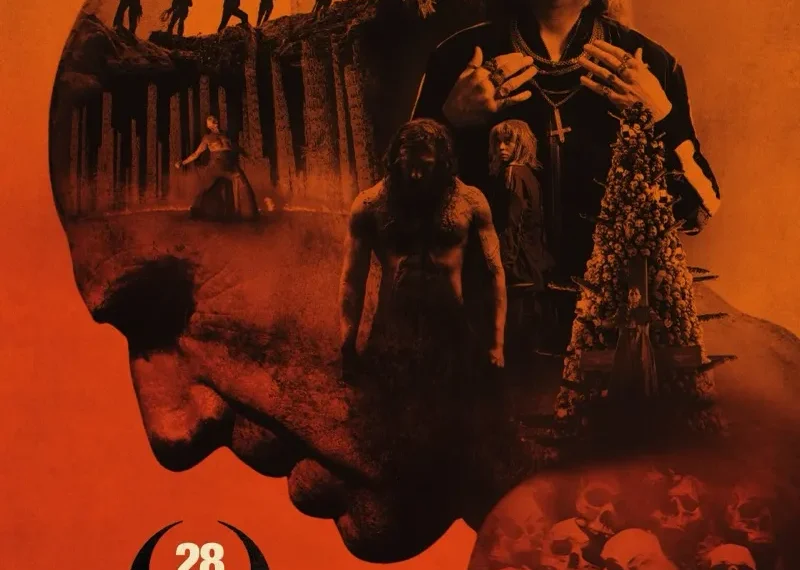

Cast: Ralph Fiennes, Jack O’Connell, Alfie Williams, Erin Kellyman, Chi Lewis-Parry

Genre: Horror

Director: Nia DaCosta

In Irish Cinemas: Now

28 Years Later: The Bone Temple doesn’t just push the franchise forward, it gleefully drags it sideways, kicks in the ribs of its own mythology, and dares you to follow. This is not a film interested in preserving the lean, panic-driven identity of 28 Days Later. Instead, director Nia DaCosta and writer Alex Garland turn the series into something stranger and more feral: a post-apocalyptic fever dream obsessed with belief, performance, and the human need to invent meaning once the world has already ended.

At its emotional centre is Spike (Alfie Williams), no longer the sheltered child we met before but a self-imposed castaway. He has abandoned safety and kin not out of rebellion, but out of curiosity, a desire to understand what kind of adult can exist when civilisation has collapsed into myth and violence. Williams plays Spike with a quiet, wounded alertness, as if the boy is constantly measuring how much humanity he can afford to keep without getting himself killed.

The film’s gravitational force, however, is Ralph Fiennes. His Dr Ian Kelson is a skeletal apparition of intellect and obsession, a man who has survived isolation not by clinging to hope, but by transforming despair into ritual. Kelson lives inside a sprawling ossuary of his own making, a cathedral constructed from human bones and scientific arrogance in equal measure. Fiennes attacks the role with ferocious theatricality, oscillating between scholar, madman, and prophet. He doesn’t simply deliver dialogue; he incants it. When Kelson spirals into monologues about pride, decay, and divinity, the film vibrates with dangerous energy.

DaCosta leans hard into tonal instability and mostly wins. Heavy metal eruptions crash into pop nostalgia, while ambient dread seeps through the score like a slow infection. The soundtrack feels curated by someone who prepared for the apocalypse by hoarding vinyl instead of weapons. Music isn’t just background here, it’s ideology, memory, and madness colliding in real time.

The film’s most unexpected gamble is its treatment of the infected. Kelson’s relationship with Samson, an Alpha strain played with imposing physicality by Chi Lewis-Parry, reframes the Rage Virus not as a simple death sentence but as a philosophical problem. Through sedation, observation, and uneasy companionship, Kelson begins to suspect that infection may not erase humanity; it may only bury it. The scenes between the two are unsettling, occasionally darkly funny, and oddly moving, suggesting a future where mercy might look like something other than a bullet.

If The Bone Temple has a weakness, it’s excess, and it knows it. Midway through, the film detonates into a parallel narrative involving a roaming cult led by Jack O’Connell’s Sir Lord Jimmy Crystal, a sun-bleached nightmare of charisma, cruelty, and empty pageantry. O’Connell plays him like a pop idol turned warlord, all glittering confidence and casual brutality. His followers, identical in name and dress, reduce murder to ritual and theology to branding. They aren’t frightening because they believe in the devil; they’re scary because belief is irrelevant. Violence is the point.

Spike’s brief immersion into this cult is among the film’s most punishing stretches. DaCosta films the atrocities with an eye toward exhaustion rather than shock; the horror comes less from fear than from the numbing repetition of cruelty. It’s here that the movie flirts with indulgence, testing the audience’s patience as much as its stomach.

But when the film finally brings its narrative threads together, cult myth colliding with Kelson’s bone-built sanctuary, everything snaps into focus. What initially feels like narrative sprawl resolves into a sharp confrontation about authorship: who gets to define meaning after the apocalypse, and how much blood must be spilt to make others believe it. The final act is grimly funny, intellectually vicious, and unexpectedly clarifying, capped by a final appearance that quietly reconnects the film to the franchise’s past.

Visually, The Bone Temple is expansive and controlled, favouring vast, empty landscapes over the claustrophobic urgency of earlier entries. While it lacks the raw digital panic that once defined the series, it compensates with scale and composition. Hildur Guðnadóttir’s score is the film’s secret weapon, mournful, droning, and liturgical; it treats the end of the world like a funeral that never reasonably concludes.

This is not a comfortable sequel, nor a clean one. It’s bloated, abrasive, and often deliberately alienating. But it’s also fearless. 28 Years Later: The Bone Temple isn’t content to scare you, it wants to argue with you, unsettle you, and leave you staring at the wreckage of faith, science, and performance long after the credits roll. And towering over it all is Ralph Fiennes, howling into the void, daring the franchise and the audience to follow him somewhere truly unholy.

Overall: 7/10