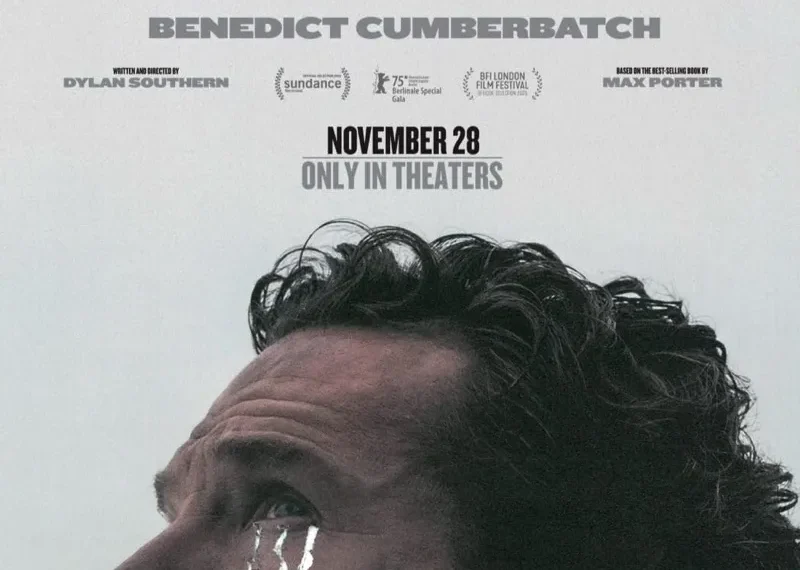

Reviewed on 27th January at the 2025 Sundance Film Festival – Premieres Section. 98 Mins.

Cast: Benedict Cumberbatch, Henry Boxall, Richard Boxall, David Thewlis, Eric Lampaert

Genre: Drama

Director: Dylan Southern

In Irish Cinemas: 21st November 2025

Crows seem to stir at the edges of Dylan Southern’s first narrative feature, a ghostly tale about a man in midlife trying to weather the shock of losing his wife, the mother of his two sons, without warning. Pinning down its genre is slippery work; it hovers somewhere between social realism and uncanny horror, as if Ken Loach had conjured The Babadook after a particularly troubled dream. Southern, best known for immersive, pulse-driven music documentaries like Shut Up and Play the Hits (2012) and Meet Me in the Bathroom (2022), transfers that same bruising immediacy to a story built from raw nerves and unresolved grief. For all its craft and emotional intelligence, The Thing with Feathers is destined to polarise: some viewers who carry their own traumas may find it powerfully cleansing. In contrast, others may recoil at its unflinching, near-perfect rendering of loss.

This is one of those films where no one is granted the luxury of a name. The father is “Dad.” Benedict Cumberbatch plays him as a rumpled, quietly volatile artist who bristles at labels; some call his work comic books, others graphic novels, though he finds the latter “pretentious.” His creations bleed into the film’s stunning opening credits, where a jittery charcoal pencil scratches furiously across stark white paper, a sense of confinement sharpened by Southern’s choice of the tight Academy frame. Disjointed, mournful phrases — “Sad Dad,” “She’s gone” — drift across the imagery of black-plumed birds, so the moment the screen falls into darkness and a funeral emerges through sound alone, it comes less as a shock than an inevitability.

“I thought you both did really well today,” Dad tells his two young sons, gently confirming the truth we’ve already felt pressing in. Even without his words, the film’s look betrays the absence hanging in the house. A place built for laughter shouldn’t be lit like a Vermeer interior. When Dad’s brother drops by, he reaches for a more contemporary comparison: “It’s like Tracy Emin’s kitchen in here,” nodding toward the artist’s notorious My Bed installation.

Dad tries to hold the remnants of their life together, getting the boys to school, keeping them fed, and reading to them at night (though the Baba Yaga folk tale might be the least advisable bedtime story for shattered children). But memory keeps ambushing him. We never see what happened, but the sound of it punches just as hard: the blood, her body on the floor, the sudden stillness of someone who is no longer breathing.

It’s around this fracture point that the film’s antagonist appears. Crow, voiced by David Thewlis, is one of Dad’s illustrated characters who suddenly steps off the page and into his real, collapsing world. And Crow has no interest in healing. Dad’s therapist urges him toward acceptance, toward boxing up the past and gradually learning to carry it. Crow, by contrast, prescribes chaos. He needles, he mocks, he lashes out — therapy by way of emotional demolition. “Come on, do your worst,” Dad snarls. “No,” Crow replies calmly, “I intend to do my best.”

What follows is a near-duet of brutality and confession, broken only by intrusions from the outside world. Southern captures this frenetic internal war with startling precision, most memorably in a drunken, unhinged sequence set to Screamin’ Jay Hawkins’ “Feast of the Mau Mau.” Being birthed from Dad’s psyche, Crow knows precisely where to strike. He jeers at Dad’s progressive ideals and, more viciously, ridicules his art as “pathetic,” comparing it to a Vettriano — a jab that lands even harder than the Emin quip.

The film gradually takes shape as a portrait of a man collapsing inward. Dad’s unravelling is portrayed with quiet authenticity: the ignored phone calls, the dread of opening the door, the refusal to accept what’s final. In one of the film’s most devastating choices, his wife’s face is never clearly shown, blurred, withheld, half-remembered, a perfect cinematic metaphor for grief’s cruel fog.

As a piece of filmmaking, The Thing with Feathers is extraordinary, a bold announcement of Southern’s arrival as a narrative auteur. As a viewing experience, though, it may prove too raw for some, a beautifully made meditation on mortality that mesmerises even as its truth cuts deep.

Overall: 6.5/10