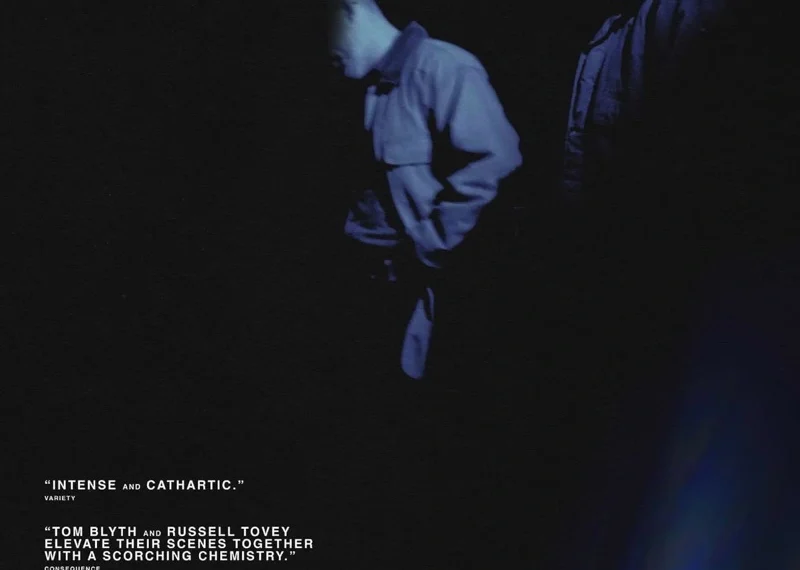

Reviewed on 30th January at the 2025 Sundance Film Festival – U.S. Dramatic Competition 95 Mins.

Cast: Tom Blyth, Russell Tovey, Maria Dizzia

Genre: Drama, Romance, Thriller

Director: Carmen Emmi

In Irish Cinemas: 10th October 2025

Tom Blyth and Russell Tovey Smoulder in a Tense 1990s Queer Entrapment Drama

Carmen Emmi’s debut film “Plainclothes” dives into repression, desire, and the moral rot of police stings targeting gay men.

Set in mid-1990s Syracuse, New York, Plainclothes unfolds like a slow fever part erotic thriller, part moral reckoning. First-time filmmaker Carmen Emmi draws from a shameful chapter of American policing, when undercover stings ensnared men cruising for sex in public restrooms. For Lucas (Tom Blyth), a rookie cop chosen to pose as bait, the assignment becomes a brutal confrontation with his own closeted desires. His growing fixation on one particular man (Russell Tovey, heartbreaking and magnetic) pushes him toward a dangerous self-awakening.

The film opens to the unmistakable pulse of OMC’s “How Bizarre” echoing through a mall food court, a perfect timestamp of 1996. Lucas sits alone, scanning the crowd, his handsome face and tense stillness inviting attention. The rules of the sting are strict: no words, no touching, no crossing the line. A look, a nod, a step into the men’s room, that’s all it takes. When a man exposes himself, Lucas exits, signalling his colleagues to rush in. It’s legal, technically. But it’s also an entrapment, a state-sanctioned humiliation campaign against men living in fear.

That Plainclothes takes place less than thirty years ago is quietly horrifying, especially in a political moment when hard-won LGBTQ rights are once again under siege. The film’s premise echoes real historical witch-hunts from police raids on gay bars to the 1953 arrest of legendary British actor John Gielgud, caught soliciting an undercover cop in a Chelsea public toilet mere months after being knighted. Gielgud’s disgrace became tabloid fodder; he survived, but countless others didn’t. Emmi’s film honours those unspoken tragedies through its portrait of men suffocating in silence, desperate for connection yet destroyed by shame.

Blyth’s Lucas embodies that torment with unsettling precision. He’s a second-generation cop from a working-class family, proud but repressed. His only act of honesty, confessing his attraction to men to his sweet, unsuspecting girlfriend (Amy Forsyth), ends the relationship. With his father dying and his mother (Maria Dizzia) clinging to family stability, Lucas swallows his truth. That repression metastasises into obsession once he meets Andrew (Russell Tovey), a soft-spoken, married administrator who catches his eye during a sting operation. When Andrew, whistling “When the Red, Red Robin Comes Bob, Bob Bobbin’ Along,” enters a restroom, Lucas breaks protocol and follows — a transgression that detonates his fragile equilibrium.

Their subsequent encounters, movie dates at Syracuse’s Landmark Theatre, secret rendezvous on a forest trail, and illicit trysts in a parked car are shot with aching intimacy. Emmi and cinematographer Ethan Palmer capture both the thrill of first genuine desire and the terror of being seen. For Lucas, these moments are a revelation; for Andrew, they’re a dangerous indulgence. “I don’t see guys twice,” he warns gently. But Lucas can’t let go. His longing curdles into surveillance as he runs Andrew’s plates through the police database, desperate to turn a brief encounter into something lasting. The fallout is painful, inevitable, and strangely liberating.

Plainclothes stumbles, at times, under the weight of Emmi’s formal ambition. The film’s lo-fi video textures, jarring sound design, and jittery editing are intended to mirror Lucas’s unravelling psyche. Still, they occasionally distract from the raw emotional truth conveyed by Blyth and Tovey. When the camera lingers in silence, in the charged space between two men, the film finds its pulse. Emmi’s aesthetic excess sometimes obscures what the actors make painfully clear: the corrosive cost of living a lie.

Still, what lingers is empathy for the men caught between duty and desire, for the years lost to secrecy and fear. The film situates itself among a lineage of queer cinema that has mapped desire in the unlikeliest of spaces: Frank Ripploh’s Taxi zum Klo, Sebastian Meise’s Great Freedom, and even George Michael’s gleefully defiant “Outside” video, which turned a public restroom into a glittering disco of liberation. But where those works reclaim pleasure, Plainclothes lingers in the ache before freedom, the claustrophobia of being watched, and the yearning to finally stop hiding.

Anchored by two riveting performances and shot through with compassion, Plainclothes is a bruising, tender portrait of men taught to fear their own reflection. It’s a story of entrapment by the state, by the closet, by the mirror and the slow, painful work of breaking free.

Overall: 7.5/10